Mario Guagliano –

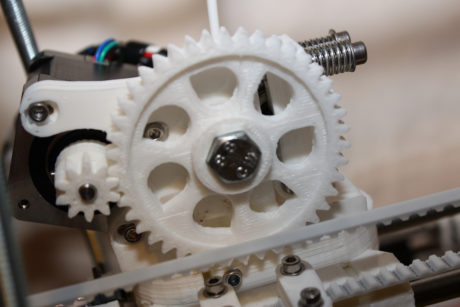

One of the major innovations in the industrial production of the last quarter of last century was the different approach to the problems concerning the assembly and its optimization in terms of time and costs. In those times, also due to the higher labour cost in the Countries characterized by older industrialization, they started devising the assembly as an important phase in determining the production cost. Deserving, then, thorough analytical analyses and the definition of criteria able to evaluate, already in the initial project phases, the impact of the different possible solutions and to compare them one another in quantitative terms, not connected with individuals’ experiences or with the standard “…we always did so, why should we change?..”. In other words, they were the development years of the Design for Assembly (DfA), then evolved into the Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DfMA), when it was realized that it was necessary to look jointly at production and assembly, since inherent costs were strictly linked one another. Moreover, in those years Boothroyd developed the homonymous technique based on the definition of the assembly efficiency, ratio between the minimum necessary theoretical time to assemble a system and the real one. Technique featuring the quality of the possible application even in presence of partial project data and, therefore, in the initial design stages permitting to assess, at least in comparative terms, different solutions and to suggest modifications when their impact on the development time and related costs is modest. Thanks to the application of that technique, Ford made great strides in competitiveness: it is anyway worth reminding that the front bumper of a Ford model was composed by just 10 pieces while a similar GM model consisted of about 100 parts, with a 40% productivity gap. We can mention similar examples, anyway, also in other industrial sectors, such as household appliances’ or, more in general, wherever manufacturing volumes are relevant. The application in canonical form of DfMA rules was, perhaps, less strong in other sectors with lower manufacturing volumes but certainly the focus on the assembly optimization was not less felt. Nevertheless, it seems that for some years now the attention to assembly has decreased, as if there was nothing important to innovate and such techniques had become routine, while the focus has shifted to the disassembly phase, also because we have to cope with the more and more severe laws for the environment protection. In the middle of this absolute calm, however, something is changing. The advent of additive technologies has allowed the development of complex parts and, at the same time, of new assembling solutions, once unfeasible. Besides, the development of such technologies has highlighted the surface accuracy problem, in particular of internal ones, hardly treated in the aftermath just owing to accessibility troubles. This can make the implementation of open parts convenient or necessary, then turning to new junction solutions. In Delft, a research team is working at the development of techniques that derive from origami: in other words, the processing of flat surfaces to achieve 3D complex parts by joining the extremities of such surfaces. In the specific case, shape memory materials are exploited to make complex three-dimensional structures and to assemble them, but other proposals are under development, with the only limit of fancy and creativity. In short, the advent of additive technologies is likely to generate relevant developments for the assembly, too; it is worth following and not neglecting them.